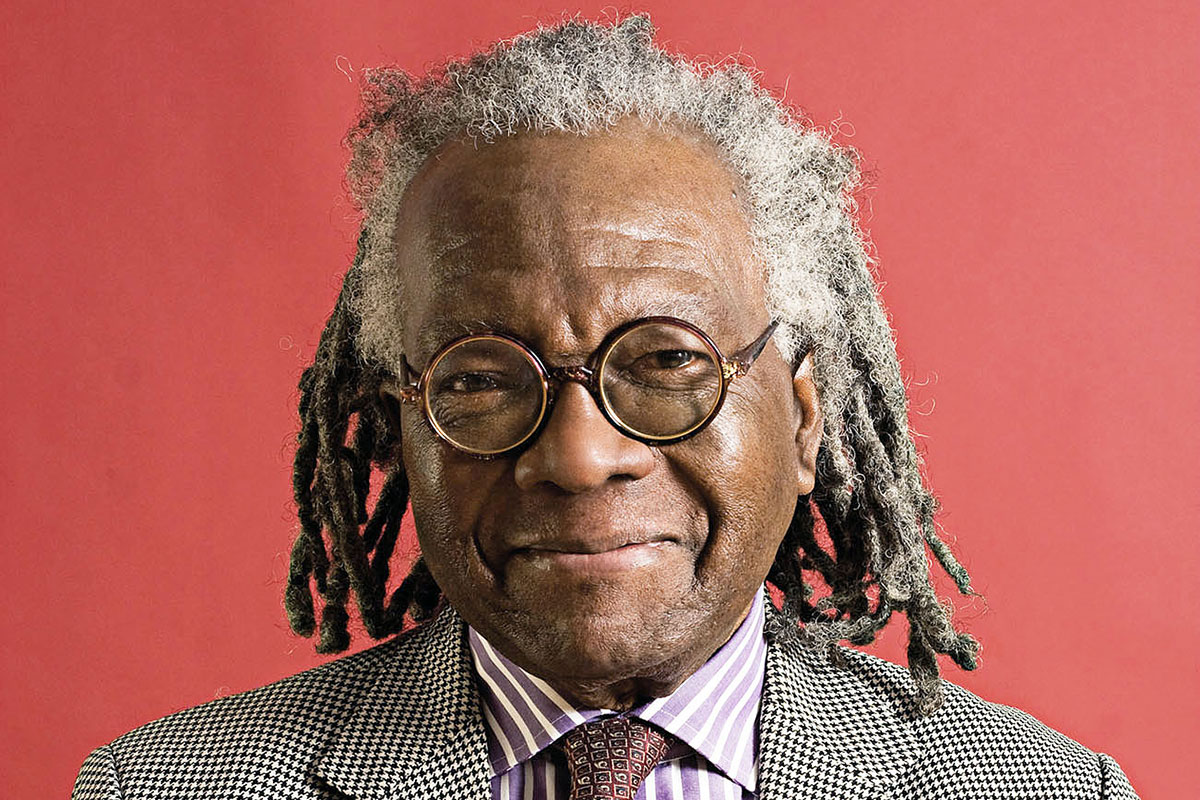

Canadian literature recently lost one of its bright lights with the passing of Barbadian-born and Toronto-based novelist Austin Clarke on June 26, at the age of 81. An award-winning author, essayist, journalist, and poet, he was the recipient of the Scotiabank Giller Prize, the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize, and the Trillium Book Award for his 2002 novel The Polished Hoe. Born in Barbados, Clarke immigrated to Canada in 1955 to study at the University of Toronto.

Throughout his life’s work, which spans eleven novels, eight short story collections, six memoirs, and two poetry collections, Austin Clarke, known as “Tom” by those close to him, blazed a trail by recounting the stories and experiences of Afro-Caribbean immigrants in Canada.

“Writing is my life,” he once said. “Writing has been a mainstay and the most important aspect of my life.”

A trailblazer and mentor

Despite describing writing as “by definition a narcissistic quest,” Clarke was never selfish with his gift. He was just as much committed to sharing its fruits with the world as he was to mentoring young writers, offering guidance and encouragement in helping to groom the next generation of authors.

“His great passions were food, for drink, but much more than that for young writers across race and class and gender, whom he would have to his home and mentor [unselfishly], reading manuscripts and offering his feedback,” said Professor Rinaldo Walcott from the University of Toronto, a long-time friend of Clarke’s.

According to fellow novelist and friend Cecil Foster, “He was always so interested in the craftsmanship of writing” and was quick to chastise his peers when he felt they were not writing enough. Clarke had a deep respect for his fellow writers advancing the discourse and literature about multicultural Canada, such as Cecil Foster, Dionne Brand, George Elliott Clarke, and Lawrence Hill. “We are really standing on his shoulders,” said Foster.

The Black Canadian experience is part of the national fabric

“The social and economic problems that define the Jane/Finch and Monarch Park in Scarborough, Regent Park, St. James Town, and Thorncliffe Park are not a sovereign Black problem; but are a Toronto problem,” Clarke said in his spring of 2010 Convocation address at York University. He warned against condemning the Black ghettoes and instead called on “shedding tears that your Black neighbours have once again been caught outside the net of omniculturalism. They have killed another brother, another sister. Why do White neighbours only mourn White victims?”

His 2008 novel, More, winner of the City of Toronto Book Award, delves into the struggles of Caribbean immigrants in Toronto in the face of racial exclusion, poverty, violence, and exploitation. The protagonist, Idora Morrison, is a Black Caribbean immigrant in Toronto living in a rented basement apartment on Shuter Street, just before Sherbourne. She immigrated to Canada 25 years prior to seek a better life. But instead, she found herself with a deadbeat husband who left her alone to raise her son, BJ, who ended up being pulled into a life of crime. The book takes a journey into Idora’s mind as she comes to grips with the realities, fears and hopes of her existence in Canada.

“The significance of More and myself is that we both live on the same street,” Clarke revealed in a 2012 Toronto public reading of the book. “In the ghetto, Shuter Street. Of course, with the number of developers invading the territory, I doubt if you can call it anymore the ghetto street,” he added.

In other writings, Clarke also speaks about his own experiences as a Black man living in Toronto, including walking into a barber shop only to be told: “We don’t cut niggers’ hair here.”

Clarke only became a Canadian citizen in 1981. When asked why he waited so long, he replied: “I was not keen on becoming a citizen of a society that regarded me as less than a human being.”

Through his pioneering contributions to Caribbean-Canadian literature, the 1998 inductee to the Order of Canada has paved the way so “that we can begin to recognize in this country that Black life is not singular, is not just lived for Black people, but that it is something that deeply enriches this place,” as Rinaldo Walcott said.

Breaking the colonial mental chains

Clarke cited author Frantz Fanon, who examined the psychology of racism and colonialism in his seminal 1952 book Black Skin, White Masks, as a major influence “because of his understanding of the Black community in Africa and the world, and his understanding of what it means to be Black in a White society.”

Despite being raised as an Anglican in his native Barbados under a British colonial system, Clarke was much influenced by and participated himself in the American civil rights and Black nationalist movements during the 1960s. He notably interviewed and befriended Malcolm X in 1963.

From the late 1960s until the early 1970s, Clarke spent several years in the United States teaching and helping set up Black studies programs at Yale, Brandeis, Williams College, Duke and the universities of Texas and Indiana.

His tenth book, The Polished Hoe, explores the slavery and colonial legacy of Barbados. In the book, he refers to his home island as “Bimshire.” Before obtaining its independence from Britain in November 1966, Barbados was a British colony. The novel itself is set in the 1950s. Through the life experiences of a woman, Mary-Mathilda, Clarke examines the collective experience of a society characterized by slavery.

As it is often the case for countries ridding themselves of colonial powers and finding their identity and rightful place in the world, Austin Clark’s literary body of work, as well as his own life, navigates often complex cultural waters.

As George Elliott Clarke recently penned, “[Austin Clarke] was never able to shake his private school elitism or his love of the Latin and good grammar he associated with school and church, or his love of good suits and good drink that he associated with the WASP elite.”

Perhaps, that’s precisely why he was so great at capturing the wide spectrum of nuances and faultlines inherent in the experiences of immigrants forging their way into the ill-fitting system of a dying cultural empire bursting at the seams. A two-founding-nations-utopia begging to be redefined, rebuilt, through a new collective consciousness.

A funeral service will be held at Toronto's St. James Cathedral on Friday, July 8, at 11:00 am.