|

“Imagination is more important than knowledge,” Albert Einstein once said. James Earl Chaney was 21 years old in 1964, shy, energetic and ambitious by the standards of the time: he went to Junior College and was pursuing an apprenticeship as a plasterer. Racial discrimination, after all, also limited the dreams that young black men could dream back then. No thoughts of becoming a governor of his home state of Mississippi or a U.S. Supreme Court justice entered James’ mind, I am sure. The demands of daily life in the Mississippi of the 1960s must have stifled his smile and restrained his enthusiasm. But certainly not too much to the point of preventing action; James was too interested in his community, his country and its future. So he volunteered at the offices of the Congress On Racial Equality (CORE), an organization dedicated to obtaining civil rights for African Americans through nonviolent activities such as student sit-ins, freedom rides in many southern states, and journeys of reconciliation that brought blacks and whites together. |

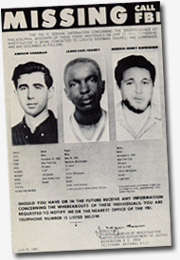

The FBI poster requesting information on James Earl Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner. |

CORE was also known for organizing massive voter registration campaigns such as Freedom Summer in 1964. The ultimate goal of all these organizations (including the NAACP) was the acquisition of full citizenship for all African Americans and other minority groups. Full citizenship had, at its core, the legal right to vote in municipal, state, and federal elections. It is through these activities that James Earl Chaney met two young New Yorkers: Andrew Goodman (20 years old) and Michael Schwerner (24 years old), who also volunteers at CORE.

On June 21st, 1964, the three men visited Mt. Zion Methodist Church, firebombed by the Ku Klux Klan because it was used to help register blacks to vote. As they drove back to the offices of CORE, they were stopped by a deputy Sheriff, let go and then stopped again. This time, the KKK mob was waiting. They were pulled out of their car and brutally murdered. It took the FBI 44 days to find their bodies, and when they did, the headline of the local newspaper the next day read:

“The Nigger was found on Top!”

Many more will see the same fate in the Deep South of the United States before the Voting Rights Act became law in 1965, and even then, disenfranchisement continued. The shenanigans of Florida “dimpled chads” in 2000 are the latest example.

In other parts of the world, men and women have struggled to earn the right to vote. In South Africa, for instance, the African National Congress (ANC), whose first main agenda was to protect the right of blacks to vote in the Cape province, saw most of its leadership sent to prison on mostly fabricated charges while others were either killed or exiled.

Also, here in Canada, the Canada Elections Act (passed by the conservative government of John Diefenbaker) effectively extended voting rights to all citizens regardless of race and gender only in 1960.

So it is with images of James Earl Chaney, Andrew Goodman, Michael Schwerner, Steve Biko and Oliver Tambo in my head that I walked up Spadina Road on Wednesday evening to attend the “All Candidates Meeting” for my federal riding of St-Paul''s. I read the literature and visited some of the candidate websites. I also watched the party leaders’ English language debate on Monday night. But I wanted to see the people who will be speaking on my behalf in parliament for the next few years.

The evening was dull, as these things usually are. Carolyn Bennett, the Liberal incumbent, sidestepped many of the questions, sticking to her voluminous stack of notes. Peter Kent, the Conservative candidate, spoke in broad strokes and avoided specifics except when pressed on the issue of abortion. The NDP and the Green Party candidates appealed to the participants’ emotions, peppering their answers with self-deprecating humour. For the most part, all the candidates stuck to generic political platitudes: “We care for the working man and woman!”, “We can achieve results!”, “Vote for change!”

But as I left the building, I was happy to have seen the fake smiles, heard the tired rhetoric and not fallen asleep. Nobody said democracy had to be entertaining, after all. The discussion also allowed me to make a final decision on who I will be voting for on January 23rd. Most importantly, I was happy that, in my very small way, I was honouring the memory of James Earl Chaney and all those who died so we could earn the right to vote.

To get information on the candidates in your riding or for other elections information, visit www.elections.ca