Nine years before Rosa Parks became known as “the first lady of civil rights” in the United States by refusing to move to the back of the bus in Montgomery, Alabama—triggering the landmark Montgomery Bus Boycott—an African-Canadian woman named Viola Desmond made a consequential act of defiance that would shed important light on Canada’s own segregationist history.

On November 8, 1946, she challenged a New Glasgow, Nova Scotia, segregated movie house, the Roseland Theatre, by refusing to leave the white-only main floor seating area. She was dragged away forcibly by the theatre manager and a police officer, spent a night in jail, was tried the next morning, convicted and charged $26. Her courageous act led the government of Nova Scotia to repeal, in 1954, the laws that allowed segregation.

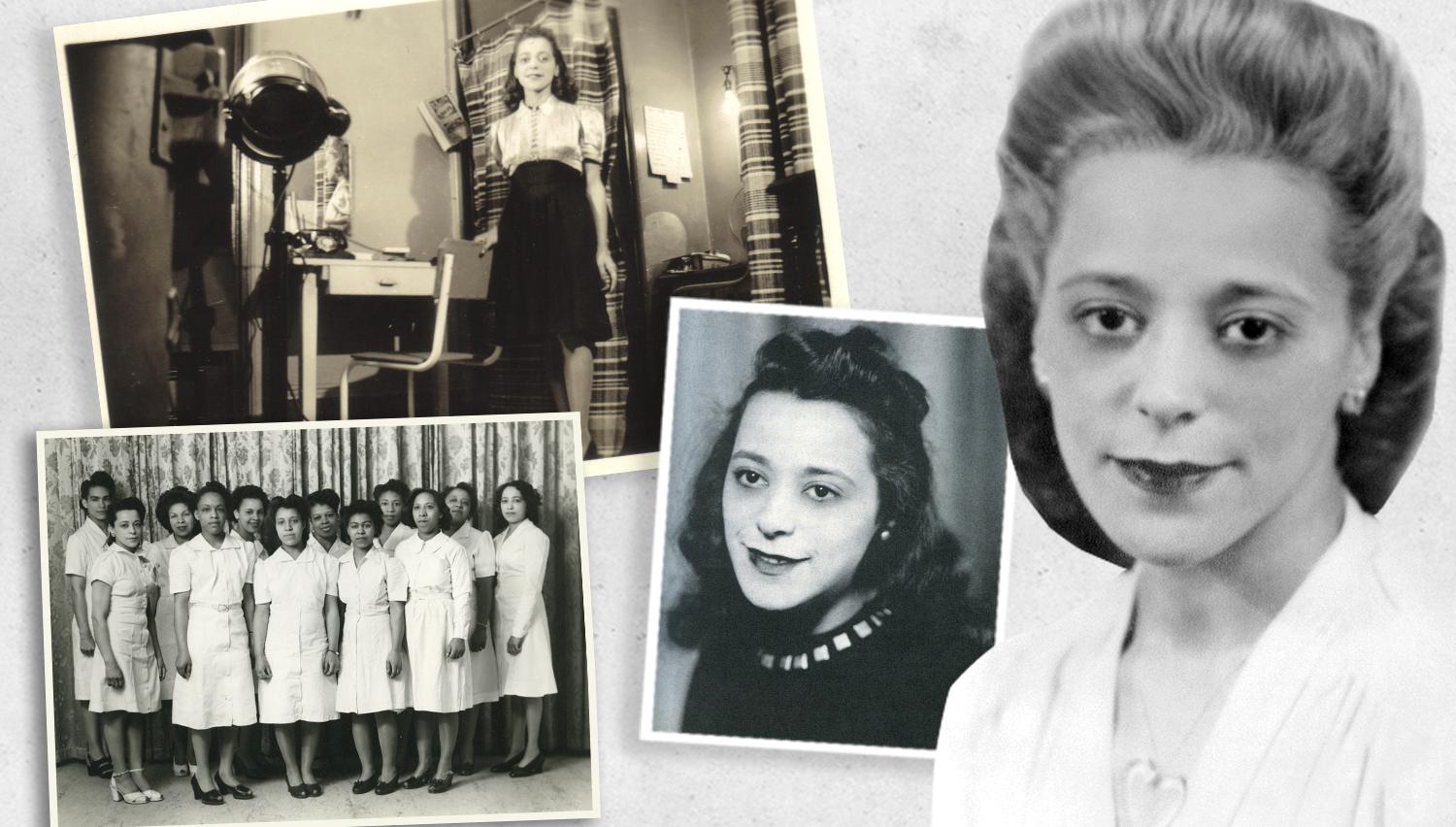

Earlier this week, on December 8, 2016, Viola Desmond was chosen as the first Canadian woman and first African-Canadian to appear on Canadian currency, the $10 bill. Replacing John A. Macdonald, Canada’s first prime minister, the new note will be issued in 2018. Desmond was chosen from a shortlist of five women, which was itself trimmed down from over 26,000 submissions from Canadians who responded to a submission open call.

The effort followed Prime Minster Justin Trudeau’s decision, announced on International Women’s Day last March, to feature a woman on the $10 banknote.

The announcement was made by Finance Minister Bill Morneau, in the presence of Wanda Robson -- the sister of Viola Desmond -- at a ceremony at the Canadian Museum of History in Gatineau, Quebec.

Unsilencing the past

‘It’s a big day to have a woman on a banknote, but it’s an especially big day to have your big sister on a banknote,’ said Ms. Robson. ‘Our family is extremely proud and honoured.’

While the Canadian and international media’s news headlines have been highlighting the important fact that Viola Desmond is the first woman to grace Canadian currency (aside from the monarch, Queen Elizabeth II), the fact must not be lost that her blackness, and her stand in the face of bigotry, is at the root of the agency-affirming movement she unleashed.

Canada has a long history of slavery, as well as employment and housing discrimination. 1946, Nova Scotia operated very much on a day-to-day basis through a segregated framework.

As Sgt. Craig Smith (RCMP, Cole Harbour, Nova Scotia) says in the documentary Long Road to Justice - The Viola Desmond Story (shared below):

“The only way in which you help to dispel some of the prejudices and some of the discriminatory actions and things that go on is to alleviate some of the fear that is out there. How do you alleviate the fear? You alleviate the fear by educating people so that I know as much about you and your history as you know about mine. If we can instill that in the youth, if we can educate the youth that we’ve all played a part in Canadian history, and we’ve all played a part in contributing to this wonderful country that we have; and that we all need to be respected because of that, then Viola Desmond’s legacy will live on forever.”

The making of a trailblazer

Born in 1914, Viola Desmond grew up in a family active in Nova Scotia’s black community. Trained as a teacher, she later joined her husband’s barbershop on Halifax’s Gottingen Street -- opening her beauty parlour wing and embarking on a business venture as a beautician.

However, on account of her race, she was not able to train as a beautician in Halifax. Thus, she set out to Montreal, New York, and Atlantic City to learn from some of the top black beauticians of her time. In New York, she trained at a school founded by the first African-American millionaire, Madame C.J. Walker.

When she returned to Nova Scotia, in addition to her own salon, she set up her Desmond School of Beauty Culture and became a mentor to young black women across the Maritimes and Quebec. She was determined to give black women the option she didn’t have of receiving proper training at home. Each year, her school graduated as many as fifteen women who had all been rebuffed by whites-only training schools. These graduates, in turn, provided jobs to other black women in their communities.

Beauty schools were one of only a few ways black women of the time in the U.S. and Canada could build a business and prosper. Since white beauty salons had no interest in catering to African hair and skin types or learning special techniques, the opportunities were widely open for black beauticians to serve their own communities.

Desmond also developed her own line of beauty products, Vi's Beauty Products, which she marketed, sold and distributed herself. As a result, she was often on the road crisscrossing the Maritimes setting up franchises, training women and selling products.

Bravely standing up for dignity

This is how fate would bring her to unexpectedly spend the night in New Glasgow, Nova Scotia, on November 8, 1946 -- while on her way to a business meeting in Sydney, Nova Scotia. Her car, a Dodge sedan, had broken down while on the road, and the mechanic informed her that it would take a day for the part needed to fix her car to be delivered. Not one to stay in her hotel room all evening, she decides to go see a movie, The Dark Mirror, at the local Roseland Theatre.

She asked for a main floor ticket but was sold a balcony ticket, reserved for people of colour. She proceeded to sit on the main floor but was soon approached by an attendant who informed Desmond that she couldn’t sit there because she had a balcony ticket. Arguing that it must have been a mistake, she returned to the ticket booth and asked for the main floor ticket that she had originally requested. The booth operator looked at her blankly and said: “We’re not permitted to sell main floor tickets to you people.”

Undeterred, Viola Desmond returned inside and sat back down on the main floor. This time, the theatre manager accosted her and told her it was indicated at the back of the ticket that they reserve the right not to sell tickets to disorderly people (not mentioning her race directly). After refusing to move, saying that she was not disturbing anybody, a policeman was called, and both men forcibly removed her from the theatre. Amid the rough manhandling, she sustained a hip injury and lost a shoe and her handbag.

Desmond was placed in a police car and sent to prison for the night. The magistrate did not tell her that she could apply for bail, that she had the right to get legal advice, or that her trial could be adjourned until she found a lawyer. She was dragged out of the theatre at around 7:00 p.m., and by 9:00 a.m. the next day, she had her trial.

She was found guilty of tax fraud against the Nova Scotia government for failing to pay the one-cent difference between the taxes levied between the cheaper balcony seats and the main floor tickets. She was fined $20 plus $6 in costs, which went to the Roseland Theatre manager. Nowhere was it mentioned in the court case documents that this matter was race-related. Desmond paid the fine and returned to Halifax.

A fight for justice

Once she arrived in Halifax, she began talking to people about her experience and explored what could be done. He husband, a religious man who was himself from New Glasgow, thought she should let it go and “take it to the Lord with prayer.”

But Desmond also sought the counsel of her church leaders, Minister William Pearly Oliver and his wife Pearline from the Cornwallis Street Baptist Church, who held a contrary opinion. Emboldened by their support, Desmond decided to fight the spurious charge in court. With the assistance of the Nova Scotia Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NSAACP), she hired a lawyer, Frederick William Bissett.

Word of her legal action spread further with the publication of an article in the inaugural edition of The Clarion, the first black-owned and published newspaper in Nova Scotia. The article’s writer, Carrie Best, had herself experienced discrimination at the Roseland Theatre in New Glasgow.

Despite her lawyer’s efforts, the lawsuit was unsuccessful. Soon after the trial, Desmond closed her business and moved to Montreal to attend a business college. She later settled in New York, where she died at the age of 50 on February 7, 1965. She is buried at Camp Hill Cemetery in Halifax.

Securing Viola Desmond’s Legacy

The mantle to fight for redressing the injustice suffered by Viola Desmond was later picked up by her younger sister, Wanda Robson. Through her determined work in keeping her sister’s story alive, Wanda Robson was the impetus behind the apology and pardon granted to Viola Desmond posthumously on April 14, 2010 -- the first such to be granted in Canada. Sixty-three years after that fateful day in New Glasgow, the special pardon was granted by Mayann Francis, Nova Scotia's first black Lieutenant Governor. Also present at the ceremony was the then-Premier of the province, who issued the following statement:

“On behalf of the Nova Scotia government, I sincerely apologize to Mrs. Viola Desmond’s family and to all African Nova Scotians for the racial discrimination she was subjected to by the justice system in November of 1946. The arrest, detainment and conviction of Viola Desmond is an example in our history where the law was used to perpetrate racism and racial segregation. This is contrary to the values of Canadian society. We recognize today that the act for which Viola Desmond was arrested was an act of courage, not an offence.

The government of Nova Scotia recognizes that the treatment of Viola Desmond was an injustice. This injustice has impacted not just Mrs. Desmond during her life and her family but also other African Nova Scotians and all Nova Scotians who find and continue to find this event in Nova Scotia’s history offensive and intolerable. On behalf of the province of Nova Scotia, I am sorry.”

- Hon. Darrell Dexter, former Premier of Nova Scotia

On November 8, 2010, Viola Desmond’s portrait was unveiled in Nova Scotia’s Government House.

In February 2012, Canada Post issued a commemorative stamp in honour of Viola Desmond.

More recently, in February 2016, Historica Canada featured Desmond in a Heritage Minute (shared below) featuring Kandyse McClure as Viola Desmond.